She has no symptoms of illness when the dental assistant asks if she knew she was walking around with a 103-degree fever. She answers that she did not know that, but that, now that she thought about it, she has been feeling tired. The teeth cleaning appointment proceeded as planned, but afterward she calls her husband to tell him that she isn’t feeling well. She’s gonna cancel her seminar that afternoon. She’ll see him in the evening. She drives home in discomfort. Once there, she slips into a sluggish sleep with occasional bouts of shallow breathing. Her temperature rises to 104. Her husband comes home to find her unresponsive. He rushes her to the emergency room where she is observed overnight. The next morning she is moved to intensive care.

The ER’s initial hypothesis was that she’d contracted some sort of aggressive viral pneumonia. Her vital signs begin to fluctuate: her breathing stabilizes, but then the pulse goes wild; when her pulse is finally regulated, her blood pressure drops. All that could be determined from the blood samples was that she suffered from acidosis, an accumulation of acid in the bloodstream.

That afternoon, the doctors tell her husband and two daughters that she suffered a rupture or aneurysm in her colon and highly acidic body waste was released into the bloodstream. The hospital staff is attentive and professional. They employ sophisticated computers, pumps, drips, and monitors, but they cannot not stabilize her condition. From dentist to death, the whole sequence takes forty-three hours.

An autopsy is performed. She did not die of viral pneumonia. There is no significant amount of fluid in her lungs. She did not die of a rupture or aneurysm. There is no damage to the stomach, bowels, or colon. Nothing’s wrong with her heart or brain. The final report concludes that a viral infection other than pneumonia killed her, but its exact pathology remains unknown.

Six weeks later, on a school trip to the Brooklyn Museum, Abbey is dawdling in the Great Hall, absorbed in the turquoise-black face of a sphinx. No nose, bejeweled features stripped out millennia ago, even defaced, she thinks this sculpture looks just like her. Arching eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes, chin tapering to a delicate V, it may be four thousand years old, but the polished rock looks sleek and sexy, an object Abbey would like to own.

A tap on her shoulder. Black, identifiably homosexual to Abbey’s eyes, the man has shoulder-length dreads under a Kangol cap.

“Hi, I’m Kyle. This is Fujiko. We’re with IMG. It’s a modeling agency. We represent Gisele and Naomi.” He goes on, listing names like they’re exotic travel destinations, his hands gesturing in seven directions at once. His smile is frequent.

Abbey says, “Wha? Sorry. IMG?” She’s trying to piece together why the Kangol man would be introducing someone else to her or why he’s mentioning where they work, or why they’re talking to her and no one else in the group. If they’re talking to me, there must be something wrong, Abbey thinks. Her middle class upbringing instilled in her a fear of not doing things in appropriate ways at appropriate times with appropriate people.

Her father and mother came from working class families. They took classes at Temple and Brooklyn College when they were in high school. They learned foreign languages and travelled to out of the way places for research. They got PhDs, but the family’s close relatives didn’t have steady footholds in the middle class. These relatives were the kinds of people who came to Thanksgiving dinner with a shirt caked in cat fur or who begged to borrow the family car, then would bust out a break light and not offer to pay for it. Kangol and Fujiko are violating basic tenets of her life. Abbey thinks. “Did I do something wrong?”

Abbey’s teacher approaches. She asks, “May I help you?” looking back and forth between the three, angling to bring the conversation to a close.

Abbey lies. “Ms. Howard, it’s okay. They took classes with my mom.”

The teacher frowns and returns to the herd of students.

“So, IMG? I don’t understand.”

Fujiko says, “We’re a modeling agency, but we are a lot more than just models. We represent Tiger Woods, the Williams sisters, the Pope.”

“You represent God?” For a split second, Abbey wonders if they are angels who’ve come to tell her about her mother.

“We’re like talent scouts, you know?” Fujiko goes on, “Can you come to our office today? We can tell you more. Show you around. Do you have any interest in modeling or fashion?”

The reality of what is happening begins to send shockwaves through the power plant of Abbey’s imagination, an imagination that not so long ago dwelled on the design of dollhouses and sleepovers. These were adults speaking to her about adult subjects with no reference to the desires of her father or her teachers or any other authority figures. She represses an instinct to throw her arms around these strangers who have just offered to usher her past the crowds of gawky teenagers waiting for admission into adulthood.

She goes on as coolly as she can manage, “I think we’ll be done here around four. My sister can take me. Can she come too?”

Abbey and her older sister Susanne sit in IMG’s waiting area, a wall of windows above 23rd street.

“Abbey Shaine? Fujiko’s ready for you.”

Susanne gets up, ready to follow her.

“Can you wait here? I want to do this alone.”

“Then what am I here for?”

“It’s the only way Dad would let me stay in the city. Please, Suse.”

Abbey’s sister Susanne is pissed to be missing her Columbia anthropology seminar with Mick Taussig. She claims he’s hot, wears bicycle shorts to class, and flirts with her. Susanne imagines she’s indulging Abbey’s benign teenage fantasy. She sees the trip to IMG as an act of big sisterly camaraderie in the wake of tragedy. Susanne has her seminars and post as chief editor of the Columbia Daily Spectator, hard won against that Long Island, Queen of the Jews Jordana. These are the activities and successes that dictate Susanne’s being. Not A Dead Mother. Abbey and her father are the victims of this train wreck. She’s fine.

The secretary leads Abbey back. Fujiko beckons her into a symmetrical grid of black desks. Opposite the desks are two walls filled with row after row of composite cards. Each comp card has the images and measurements of a model formatted onto a five and a half by eight and a half inch card. These are called The Boards.

You have the top shelf girls, the ones in demand, all the way down to the bottom shelf, The Floor: the ones gone AWOL, pregnant, or in rehab. The bookers take calls, inspecting The Boards, eyeing who’s trading higher, who’s due to make a move, who’s faltering after a splashy debut. It’s all cutthroat, but Abbey doesn’t notice any of this. She just sees a shrine dedicated to identically beautiful women with bookers giggling French, staccatoing Italian, and rolling Portuguese with IMG offices around the world.

Abbey wanted it.

“I know this looks exciting and fun, but it’s hard work. You’re away from your family. It gets lonely. It’s,” Fujiko emphasizes, “hard work.” She squeezes Abbey’s shoulder to get her attention, but Abbey’s imagining her card next to Gisele’s and Heidi’s.

Kyle comes up, lays a stack of stapled paper on the desk. Fujiko says, “Here’s a standard two year contract. I want you to take it home and show it to your parents.”

Abbey flips through it. Her father would never consent to any of this, and if Suse saw it, Abbey’d have to hear some gender studies rant about Charlotte Gilman and Doris Lessing. Abbey reaches into her book bag, grabs a pen, and signs.

“Great!” says Kyle.

“Well, you know, she’s still a minor. We’ll need a guardian. You really should get your parents to read it through,” instructs Fujiko.

“One second.” Abbey jumps up and walks out to Suse in the waiting room. “I need you to sign something.”

“What is it?”

“A consent form so I can get my hair-cut and have some photos taken.”

“Then can we get out of here?”

“Sure.”

Abbey takes her back.

“This is Susanne, my sister and guardian. She’ll sign.”

In modeling, for every gig a few girls are put on hold. It’s called an option.

Options pop up every day. Bathing suit shoot in Malta. Gap campaign in New York. Japanese Vogue in Sicily. Nylon cover in Berlin. You might get booked for all or none.

Whenever she gets an option, Abbey calls her father.

“Dad, I’m going to Greece. A magazine job! Elle!”

Without a trace of enthusiasm, playing up the role of widower Princeton professor, he says, “Go to the Acropolis, dear. Retrace the Panathenaic Procession.” This was how it goes. Before any job is even confirmed, she presents it to him as a done deal, stressing her success, and then he deflates her enthusiasm for the transient by reminding her of the steamroller that is time. But, she figures, at least he has some idea what she’s doing.

The summer of 2001 she lands a big option. She’ll be modeling for an artist in a spread for The New York Times Magazine.

The photographer is Taryn Simon. Simon’s notorious for her treatment of models. When Abbey asks her booker about the photog’s reputation, he barks his best Simon: “Shut the fuck up and get in the shark tank, bitch!”

Morning in Paris, still dark outside. Abbey finds the production trailer. Climbs on. Introduces herself. Joins the crew. An hour later Taryn enters. Combat boots, skinny, long stringy brown hair. She pulls her shades off. “I’m the photographer. We’re going now. It’s an hour to the location.” She stalks off, travelling separately.

The trailer pulls up to a leafy park in the banlieue. The models are called back, one at a time for hair and makeup, and then led into the woods.

“Wanna smoke?” A girl asks Abbey, Eastern Europe thick in her voice. She has black hair, pale skin and blue eyes set above high cheekbones.

“Sure. Where you from?”

“Hungary. Originally Romania. Originally Transylvania. I have like three passports.”

“What’s your name?”

“Agota.”

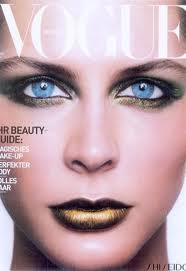

“Okay, yeah. I know your comp from the wall. You’re stunning. The cover of Vogue Beauty. Nice. I’m Abbey.”

“I’m alright. I lack symmetry. My mouth and chin. And I walk funny.”

She shifts into a few steps of her catwalk march. Abbey nods. Her walk is a little funny. There’s definitely some duck waddle in there.

“I don’t think it matters. They say my features are all over-sized.”

“But you’re American. Why you do this shit?”

A lighting assistant comes up. “Let’s go girls.” They follow him into the park.

They reach the shoot. Simon’s tripod is low to the ground, pointed toward the sky.

“Shit. That’s fucked up,” Agota says, pulling on her cigarette.

A model is suspended twenty-five feet above them. She’s dangling, Christ-like, equidistant between two trees, writhing naked in a harness.

“Shark tank,” Agota says. “Fucking cunt.”

“I’m worried about us.”

“We’re fucked.”

They’re led past the hanging model to the base of an oak tree. There are two footstools and yards of rope.

“Right, girls, onto the stools. We’re gonna tie you two ladies to either side of the tree and then when we’re ready for the shot we’ll get rid of the stools. 1-2-3. Easy.”

Agota and Abbey climb on, pressing their backs to the tree. The assistant binds them with lengths of rope around their chests and arms. Then a second coil immobilizes their calves. To keep them suspended, the rope is pulled tight. The fibers pinch Abbey’s arms and constrict her breathing to a shallow wheeze. The bark bites into her thighs.

“Okay, we gotta see if it’ll hold.”

The assistant jerks the stools out. The women sag, grating their bare skin against the bark, etching friction burns on their arms and legs. They groan.

“Sweet! Looks rad.” The assistant says.

“PUT THAT FUCKING THING BACK!” Agota demands.

Like a chastised child, the assistant grabs for the stool, trying to wedge it back in, but as he’s doing it, he starts having second thoughts, like he’s remembering instructions from the photog.

“I can’t. You slipped too much. I can’t get it back under. No room.”

“DIG OUT THE GROUND!” Agota directs.

“No. Can’t. It’ll be bad for the shot. She’ll be over soon. You can hold on.”

Abbey feels Agota’s sharp inhale straining her own chest.

A tech sets up the generator and lights, navigating around the girls with a light meter.

“We’re gonna take some test polaroids to make sure it’s ready.”

The assistant starts snapping pictures. Abbey’s unclothed from her hips down, but she can’t readjust the bunched up dress. She loses track of time. All her energy goes toward staying still. She’s sweating. She can feel the ropes swelling with absorbed perspiration.

“Agota? How you doing?”

“Shut up! Fuck. My grandparents died in wars so I can be tied to a tree?”

Abbey contemplates a flood of black and white images of Agota’s family in Nazi paramilitary uniforms, chasing Jews through the forest, Abbey’s grandfather running for his life, diving behind a tree.

Abbey’s eyes are closed against the pain when she hears Simon approach.

Simon says, “How we doing over here?”

“TAKE THE GODDAMNED PICTURE!” Agota says.

“Got it. Right.”

As the camera starts clicking, Simon says, “You ladies must love your jobs right now.”

The final image: two tiny, frail girls collapsed in a vapor of fog beneath a menacing canopy of black branches.

Two months later, airplanes crash into the World Trade Center and the editors of The New York Times Magazine deems the photos “too violent” and Abbey never agrees to model for an artist again.